Table of Contents

Have you ever dreamed of capturing your students’ attention with the sound of a bell or a clap? Would you like them to get on task as soon as they see a trigger? Perhaps you’d love to see smooth and swift transitions between activities, following preset routines that your students know by heart.

Conditioned learning is the approach that can help you achieve this ideal classroom environment.

Conditional learning—rooted in psychological theories of behaviorism—plays a significant role in education, particularly in English language teaching (ELT). It refers to the process of shaping behaviors through stimuli-response associations (classical conditioning) or rewards and consequences (operant conditioning).

While these methods are not the only ways students learn, they provide powerful tools for structuring lessons, managing classrooms, and reinforcing language retention.

This post explores how classical and operant conditioning can be applied in ELT. Practical strategies are offered while potential limitations and adaptations for diverse learners are addressed.

Understanding Conditional Learning: Classical vs. Operant Conditioning

Conditional learning is rooted in the behavioristic theory. It considers that learning happens through associations of stimuli and responses. The concept was first developed by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov. Other developments of the concept were addressed by B.F. Skinner.

A. Classical Conditioning (Pavlovian Learning)

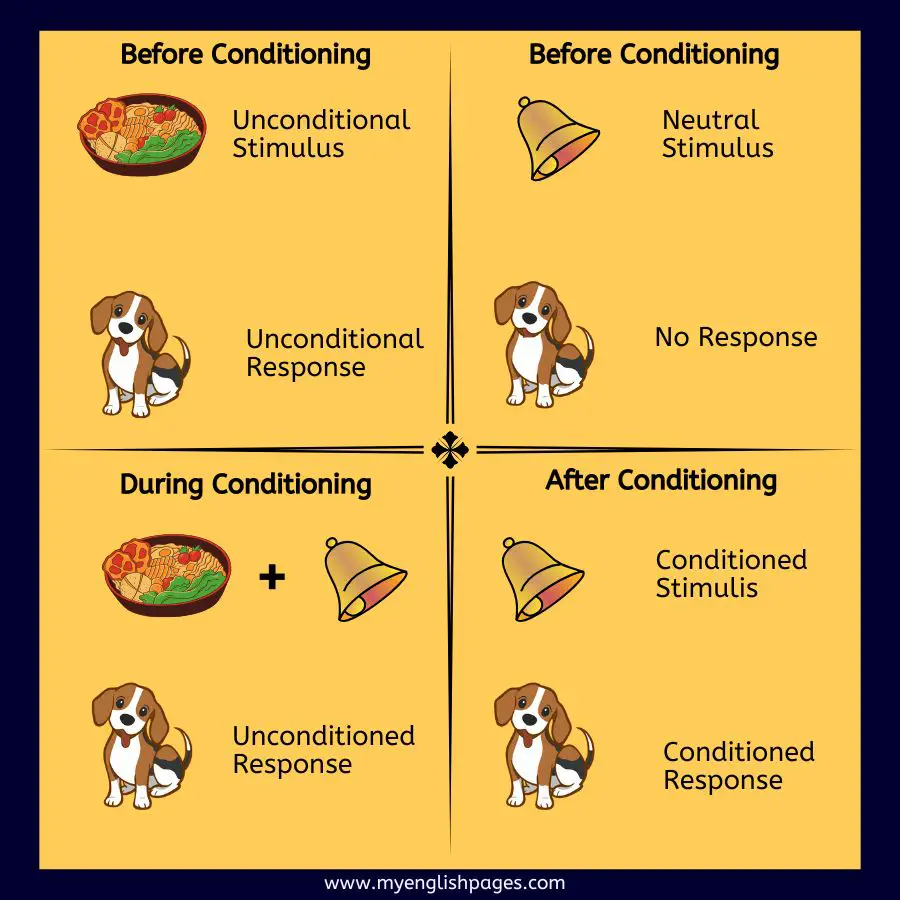

Classical conditioning occurs when a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a meaningful stimulus, leading to a conditioned response. In Pavlov’s famous experiment, dogs learned to salivate at the sound of a bell after it was repeatedly paired with food.

I. Neutral, Unconditioned, and Conditioned

Classical conditioning relies on three key components:

- Neutral Stimulus (NS)

- A stimulus that initially does not trigger any significant response related to the desired behavior.

- Example: In Pavlov’s experiment, the sound of a bell was neutral because, at first, the dogs did not salivate when they heard it.

- Unconditioned Stimulus (US)

- A stimulus that naturally and automatically produces a reflexive response (no learning required).

- Example: Food was the US in Pavlov’s study because it naturally made the dogs salivate.

- Unconditioned Response (UR)

- The innate reaction to the unconditioned stimulus.

- Example: Salivation when food was presented (no training needed).

II. How Conditioning Transforms the Neutral Stimulus

- Through repeated pairing, the neutral stimulus (bell) is presented just before the unconditioned stimulus (food).

- Over time, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS), now capable of triggering the response on its own.

- The response to the CS is called the conditioned response (CR)—a learned behavior.

Pavlov’s Experiment Breakdown:

| Stage | Stimulus/Response | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Before Conditioning | Neutral Stimulus (NS) | Bell → No salivation |

| Unconditioned Stimulus (US) | Food → Automatic salivation (UR) | |

| During Conditioning | NS + US repeatedly paired | Bell rings, then food appears (multiple times) |

| After Conditioning | Conditioned Stimulus (CS) | Bell alone → Salivation (CR) |

Similarly, in the classroom, students can develop automatic responses to certain stimuli that facilitate language learning.

For example, if a teacher consistently plays a soft melody before a vocabulary quiz, students may begin associating that melody with focused attention and readiness to recall words. Over time, simply hearing the melody could trigger their recall abilities, illustrating conditional learning in action.

Classical Conditioning in a Nutshell:

- Definition: A neutral stimulus becomes associated with a meaningful one, triggering an automatic response.

- Example: Pavlov’s dogs salivated at the sound of a bell after repeated pairings with food.

- ELT Application:

- Play calming music before reading sessions → Students associate it with focused attention.

- Use a specific phrase (e.g., “Let’s brainstorm!”) to signal creative thinking time.

B. Operant Conditioning (Skinner’s Reinforcement Theory)

While classical conditioning shapes involuntary responses through association, operant conditioning (developed by B.F. Skinner) focuses on modifying voluntary behaviors using consequences.

These consequences fall into four key categories:

| Type | Definition | ELT Example |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Reinforcement | Adding a pleasant stimulus to increase a behavior. | Praising a student after they answer in full sentences → More participation. |

| Negative Reinforcement | Removing an unpleasant stimulus to increase a behavior. | Canceling homework because the class spoke English all lesson → More English use. |

| Positive Punishment | Adding an unpleasant stimulus to decrease a behavior. | Giving extra drills for off-task talking → Less disruption. |

| Negative Punishment | Removing a pleasant stimulus to decrease a behavior. | Revising “free talk” time due to misuse → Better focus on tasks. |

Here are the major distinctions between classical and operant conditioning in practice:

- Reinforcement (Both Types)

- Strengthens desired behaviors.

- Best for: Encouraging participation, risk-taking in language use.

- Example:

- Positive: Awarding “language leader” badges for volunteering.

- Negative: Letting students skip a repetitive exercise if they achieve targets.

- Punishment (Both Types)

- Weakens unwanted behaviors.

- Use sparingly: Can create anxiety; focus on redirecting instead.

- Example:

- Positive: Brief time-out for persistent L1 use (rare).

- Negative: Losing group points for off-task behavior.

Operant Conditioning in a Nutshell:

- Definition: Behaviors are strengthened (or weakened) by rewards or punishments.

- Example: A student participates more after receiving praise.

- ELT Application:

- Positive reinforcement: Praise, stickers, or “linguist badges” for using target vocabulary.

- Negative reinforcement: Removing a homework assignment when the class achieves a goal.

Key Difference between Classical and Operant Conditioning:

While both classical and operant conditioning are behaviorist learning theories, they differ fundamentally in their mechanisms and applications:

- Classical conditioning = involuntary responses (e.g., reacting to a cue).

- Operant conditioning = voluntary behaviors shaped by consequences.

| Aspect | Classical Conditioning | Operant Conditioning |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Response | Involuntary (automatic, reflexive) | Voluntary (deliberate actions) |

| Focus | Associations between stimuli | Consequences of behavior |

| Key Figures | Ivan Pavlov | B.F. Skinner |

| Process | Pairing neutral + unconditioned stimuli | Reinforcing/punishing behaviors |

| Learner’s Role | Reacts to the environment | Reacts to the environment |

| Example in ELT | Students relax when hearing a specific song (CR) | Students participate more to earn praise (reinforcement) |

In the English language classroom, both types of conditioning can be used effectively:

- Classical conditioning helps students develop automatic responses to specific classroom cues, such as associating a teacher’s gesture with silence.

- Operant conditioning reinforces behaviors through rewards (praise, stickers, extra points) and discourages undesirable actions with mild consequences (redirection, loss of privileges).

Practical Applications of Conditional Learning in the English Classroom

Here are some examples of conditional learning in the Classroom

- Positive Reinforcement for Participation

Teachers often use praise and encouragement to condition students to participate more actively in class. If a student receives positive feedback whenever they attempt to speak English, they are more likely to engage in discussions in the future. This reinforcement strengthens their confidence and willingness to communicate. - Association of Classroom Cues with Learning Behaviors

A teacher may establish specific cues to signal different classroom activities. For example:- Flashing a green card may indicate that students should form discussion pairs.

- Ringing a bell might signal the transition from group work to individual tasks.

- Using hand gestures for silent correction during speaking activities reinforces correct pronunciation without verbal interruption. These cues become associated with expected behaviors, improving classroom management and student responsiveness.

- Using Repetitive Phrases to Trigger Responses

Many teachers use predictable phrases that condition students to react in specific ways. For instance:- “Eyes on me” → Students stop talking and look at the teacher.

- “Are you ready?” → Students respond in unison, reinforcing group participation.

- “Turn and talk” → Students immediately begin discussing with their partners. Over time, these verbal cues become automatic, making transitions smoother and reinforcing language use.

- Reducing Anxiety Through Routine and Familiarity

Language learning can be stressful, especially for shy or hesitant learners. However, consistent classroom routines—such as starting every lesson with a simple conversation or journaling activity—help students associate English practice with comfort and routine rather than anxiety. - Pronunciation: Pointing to the mouth with the tongue between the teeth, (conditioned stimulus) to trigger correct /θ/ sound production (conditioned response). If the correct pronunciation is reinforced by praise, students will likely learn how to pronounce the sound.

- Grammar: A chime sound (CS) reminds students to use past-tense -ed endings (CR), reinforced by badges or game privileges.

The Critical Role of Repetition in Language Teaching

Repetition is crucial in English language teaching according to the conditional learning theory. Here is why:

- It Strengthens Associations: Repeated pairing of cues (e.g., gestures, sounds) with correct responses solidifies automaticity.

- It Prevents Extinction: Consistent reinforcement maintains behaviors; sporadic rewards weaken conditioned responses.

- It Builds Fluency: Just as muscles grow through exercise, language skills become reflexive through patterned practice.

Here is an example:

Students who hear the chime + practice -ed endings daily for 2 weeks will self-correct faster than those with irregular drills.

Takeaway: Conditioned learning thrives on routine—structured repetition bridges conscious effort to unconscious mastery.

How to Use Conditional Learning in the Classroom

To implement conditional learning effectively in the English language classroom, teachers can:

- Establish Positive Associations

- Use consistent cues (e.g., a bell or clap for quiet time, a specific phrase for group work) to trigger desired behaviors.

- Pair new vocabulary with vivid visuals or gestures (e.g., miming “climb” while teaching the word).

- Start lessons with a low-pressure ritual (e.g., “Word of the Day” sharing) to build comfort.

- Reinforce Learning Behaviors

- Immediate Feedback: Praise precise efforts (“Great use of the past tense!”) rather than generic praise.

- Variable Rewards: Surprise rewards (e.g., “Bonus point for the first person to spot today’s grammar rule!”) sustain motivation.

- Peer Reinforcement: Encourage applause or “kudos boards” for classmates who take risks in speaking.

- Minimize Negative Associations

- Correct errors indirectly (e.g., recasting: Student: “He go.” → Teacher: “Yes, he goes to school”).

- Correct mistakes by normalizing mistakes as learning steps (e.g., “My Favorite Mistake” time to analyze common errors).

- Minimize punitive measures; instead, link consequences to natural outcomes (e.g., “If we practice now, you’ll feel confident in the interview role-play later”).

- Use Multisensory Learning Cues

- Visual: Color-code grammar rules (e.g., blue for past tense, red for present).

- Auditory: Clap syllable patterns for pronunciation (e.g., “beau-ti-ful”).

- Kinesthetic: Have students “write” words in the air to reinforce spelling.

- Leverage Repetition Strategically

- Space out practice (e.g., revisit conditioned cues weekly) to strengthen long-term retention.

- Mix stimuli (e.g., alternate between music, gestures, and verbal prompts for the same behavior) to prevent habituation.

- Fade Cues Gradually

- Once behaviors become automatic, reduce reliance on rewards/cues (e.g., shift from stickers to occasional verbal praise).

- Transition to student-generated cues (e.g., learners create their own grammar reminders).

Tip: Track which conditioned responses stick best—students may respond more to auditory (chimes) than visual (posters) cues. Adapt accordingly!

These strategies create a responsive, low-anxiety environment where language habits form organically.

Adapting for Diverse Learners

- Young Learners: Use more visual/tactile cues (e.g., a stuffed animal that “listens” only when the class is quiet).

- Teens/Adults: Tie rewards to real-world benefits (e.g., “Using these phrases will help in job interviews”).

- Anxious Students: Gradually introduce conditioning—start with low-pressure routines before high-stakes tasks.

Cultural Note: Some gestures (e.g., thumbs-up) may not translate. Always check students’ cultural backgrounds.

Limitations and Ethical Considerations of Conditional Learning

While conditioning may seem effective, it has significant limitations, particularly when applied to language learning and education.

- Overlooks Cognitive Processes

Conditional learning focuses solely on observable behavior, ignoring the complex cognitive processes involved in acquiring and using language. Learning is not simply a matter of forming associations through repetition and reinforcement; it also involves problem-solving, creativity, and internal reflection, which conditioning theories fail to address. - Non-Linear Nature of Learning

Learning does not always follow a predictable, step-by-step pattern. Language acquisition, for example, often involves sudden leaps in understanding rather than gradual accumulation through conditioning. Students may internalize language structures through exposure and context rather than explicit reinforcement. - Over-Reliance on Rewards Can Reduce Intrinsic Motivation

While reinforcement can encourage learning, excessive reliance on external rewards (e.g., praise, grades, or tangible incentives) may diminish intrinsic motivation. If students become dependent on rewards, they may lose interest in learning for its own sake. Instead, fostering curiosity and engagement is crucial for long-term success. - Limited in Addressing Higher-Order Thinking Skills

Conditioning is effective for rote memorization and habit formation, but it does not support the development of higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, and critical thinking. Complex learning tasks often require students to apply reasoning and creativity beyond simple stimulus-response associations. - Fails to Accommodate Individual Learning Differences

A one-size-fits-all approach does not work in education. Some learners thrive on social interaction, collaboration, and active problem-solving rather than conditioning-based reinforcement. Approaches such as project-based learning, inquiry-based learning, and cognitive strategies may be more effective for certain students. - Ethical Concerns: Avoiding Manipulation

Reinforcement techniques can sometimes border on manipulation if they are used to control rather than support learning. Ethical teaching practices should ensure that conditioning strategies are used to guide students in a positive and empowering manner rather than to enforce compliance or suppress independent thought.

FAQs about Conditioned Learning in Education

What is conditioned learning?

Conditioned learning is a type of learning in which behavior is shaped through associations, reinforcement, and repetition. It is based on behavioral psychology principles, particularly classical and operant conditioning, where learners respond to stimuli or consequences in their environment. This approach emphasizes observable behaviors rather than internal cognitive processes.

What is an example of conditioned learning?

A common example of conditioned learning in education is using praise or rewards to reinforce good behavior. For instance, a teacher might give students stickers for completing their homework on time. Over time, students associate completing homework with positive reinforcement, increasing the likelihood of repeated behavior.

What are the types of conditioned learning?

There are two main types of conditioned learning:

– Classical Conditioning – Learning occurs through association.

Example: A student feels anxious when hearing a bell because it signals an upcoming test (if previous tests caused stress).

– Operant Conditioning – Learning occurs through consequences.

Example: A teacher gives praise (positive reinforcement) when students participate in class, encouraging them to engage more.

What is the conditioning method of teaching?

The conditioning method of teaching applies principles of classical and operant conditioning to influence student behavior and learning outcomes. It includes strategies such as:

Using positive reinforcement (praise, rewards) to encourage desired behaviors.

Implementing negative reinforcement (removing distractions or undesired elements) to promote focus.

Applying consequences (detentions, loss of privileges) to discourage undesirable behaviors.

What are the principles of conditioned learning?

The key principles of conditioned learning include:

– Association – Linking a stimulus with a response (classical conditioning).

– Reinforcement – Strengthening behaviors through rewards or removal of negative stimuli.

– Punishment – Reducing behaviors through consequences.

– Extinction – Gradually removing reinforcement to diminish learned behavior.

– Generalization – Applying learned behavior to similar situations.

How do you use conditioning in the classroom?

Teachers use conditioning techniques to manage behavior and enhance learning:

– Positive Reinforcement: Praise students for participation or effort to encourage engagement.

– Token Systems: Giving stickers, stars, or points for good behavior or academic achievements.

– Classroom Routines: Using consistent cues (e.g., a bell for transitions) to establish structure.

– Shaping: Rewarding small steps toward a desired behavior, such as gradually improving writing skills.

– Behavior Contracts: Setting clear expectations and consequences for student behavior.

Final Thoughts: Conditioning as a Tool, Not a Rule

Conditional learning offers ELT teachers a structured way to:

- Improve classroom management.

- Boost engagement through predictable routines.

- Reinforce language retention with targeted feedback.

However, it works best when combined with communicative, student-centered methods. For example, pair conditioning techniques with:

- Task-based learning (e.g., rewards for completing real-world challenges).

- Collaborative activities (e.g., group rewards to promote teamwork).

Try This: For one week, implement one classical cue (e.g., a bell for quiet time) and one operant reinforcer (e.g., praise for volunteering). Observe the impact!

Related Pages

- Behaviorism Learning Theory

- A Comprehensive Description of Cognitivism

- The Basics of Constructivist Learning Theory: An Overview for Teachers

- Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory

- Understanding Jerome Bruner’s Constructivist Theory

- 7 Implications Of Bruner’s Learning Theory On Teaching

- Understanding Connectivism Learning Theory

- The Kaleidoscope of Learning Theories: A Concise Exploration

- Philosophy of Education for Teachers